Date First Published: July 29, 2014

Date Last Revised: July 4, 2023

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally among medical practitioners (doctors), the process at the very beginning of care is termed as “clerking”. This consists of “history taking” and “physical examination”. Other clinical care providers e.g. nurses use the term ‘assessment’. It must be realized that this process is the start of a data management cycle which consists of:

- Data collection / gathering

- Data Capture

- Data Storage

- Data transfer / dissemination

- Data Use i.e.:

- extraction

- aggregation

- analysis

- interpretation

- presentation (display)

When data is recorded on paper, the act of writing in ink captures the data. The entries are somewhat indexed as lines, pages, files and folders with paper as the storage medium. Data is disseminated by making the folders available at the point of care. The record is then perused and interpreted by the clinician.

At present computerized information systems are available to perform these processes in a more organized manner leading to enhanced benefits. Data capture is done through typing on a keyboard, selecting values of data elements of a data-entry form using a pointing device or scanning using a bar-code reader. In fact images can also be part of he record. Data is properly indexed and stored in a database. Users view the data on a computer screen. Data is distributed via a network allowing many persons to view it simultaneously.

Actually, information is generated and utilized at every step of the clinical care process including the activities of investigation, observation, monitoring, diagnosis, planning, treatment and review. Clinicians also record their plans, orders, procedures performed, observations, test results, opinions and discussions. Also, unplanned events (incidents) are recorded. Often, this is considered as ‘clinical documentation’.

Dependence of Clinicians and Clinical Practice on Data

Clinical care processes are iterative or cyclical in nature i.e. the processes are repeated as and when necessary. Therefore, as subsequent work processes are performed more information are generated.

Clinicians (i.e. all professionals involved in direct patient care) are very dependent on data already available to perform their work. Therefore, from this perspective clinical care processes should be considered as a series of data / information management activities. Being able to access the accumulated data is indispensable because a large part of clinical processes is made of cognitive (thinking) processes with data being the main input and output.

This article discusses the process of information gathering in general and specifically, data gathering at the initial part of care. Data collection for purposes of monitoring, diagnosis, treatment planning, monitoring and progress review and assessment are discussed in separate articles dealing with them.

The term “initial” is applied to the first encounter of a patient with a doctor or any other health care provider of the clinic or hospital regardless of whether he/she is a walk-in patient or a referred case. The difference is that if assessment, observation and treatment had been performed previously, the results are usually available in the referral letter and can be termed as data originating from elsewhere.

At subsequent interaction with the patient (follow up visits and encounters) data is continually collected for purposes of monitoring, progress review and evaluation.

BUILDING A PROFILE OF THE PATIENT

Patient care is not just about treating the disease but the patient as a whole. Therefore, there is a need to have sufficient information regarding the patient to allow for special considerations to be made in making decisions, implementation of care plans, communications and imparting information.

Identification

It is important to identify the patient with certainty so as to ensure that:

- The right process is performed on the right patient

- The patient’s data is assigned to the right entity in the common database and subsequently to the right medical record.

A patient is usually identified by his/her name. However, this is often not unique enough as persons can have the same name. It is the practice in health care to assign a serial non-repeated number to the person (Medical Record Number or Patient ID). If there is an existing unique personal identification number like the National Registration Identification number, this may serve the same function alternatively or be the secondary identifier. Some characteristics of the person must be known before this unique number is given. Subsequently, confirmation of identity is based on a set of data rather than one data element. These characteristics include a photograph, gender, age, ethnic origin and home address.

Demography, Anthropometry and Social Background

Demographic data such as age and gender have other uses besides confirming identity. Anthropometric data such as height, weight and body surface area allow for the patient to be grouped into physiologic categories. They can be used to calculate certain parameters and allow comparison with expected standards e.g. body mass index and growth percentile or doses such as requirements for dietary intake, fluid, drugs and radiation. Other parameters like educational level, ethnic origin, languages spoken, occupation and location of abode, give an idea on the social background of the patient enabling the care provider to understand how the illness affects the patient’s life and his ability / willingness to comply with treatment programs.

Acquiring Complete Information Re: Health Status

The total care of a patient cannot be achieved by knowing the diagnosis of the present illness alone. The clinician needs to know the health status of the patient before and immediately after he/she is affected by the illness. With this information, he/she is better able to determine the severity of the effect of the disease on various physiologic systems and subsequently to provide supportive therapy.

Pre-Morbid Health Status

It is good to know the health status of the patient before he/she is affected by the illness. An important aspect is the nutritional status. Other aspects include level of physical activity, social interaction and psychological outlook. In children, the developmental status may contribute to or affect the current illness. Most importantly pre-existing illnesses including chronic diseases and unresolved previous illnesses or injuries need to be carefully evaluated. The care provider must be aware of whatever treatment that the patient is receiving currently, especially drugs and how well these have controlled the effects or modified the course of the illnesses.

Psycho-social Status

The patient’s psycho-social status and level of education needs to be gauged; because these will impact on his/her understanding of the illness and its management. It would also make it easier for the care provider to communicate with the patient and ensure that the patient accepts, complies with and is satisfied with various aspects of care given.

CREATING A RECORD OR LOG OF EVENTS

Based on professional and legal requirements, clinicians must capture and store data regarding events or incidents experienced by the patient and the processes performed in managing him/her. The greater part of the stored data is designated as being part of the Medical Record. The clinician also needs to record the intended case management objectives and plans. Recorded data can be used for quality control and for ensuring continuity of care. The data regarding a patient or the aggregated data of a group of patients is valuable for administrative reviews or audits, inquiries, quality measurement, teaching-learning activities and research. Recording the data is also necessary for legal and professional purposes to demonstrate transparency, accountability, compliance with regulations and conformance to professional ethics. The medical record should also make evident the roles, responsibilities of various care providers vis-à-vis the patient and also the relationships between the care providers.

The data in the Patient Information Database and subsequently the medical record is arranged in chronological order and grouped according to periods such as episodes, sessions, visits, encounters and events (planned and unplanned). Some auxiliary data need to be collected and recorded as well. These include:

- time & period (beginning and end of a session, duration of transactions).

- sequence,

- context, occasion,

- location.

- identities of persons involved.

Mechanisms must be in place to record tasks performed and the results either manually (via forms and charts) or automatically when those are performed by machines .

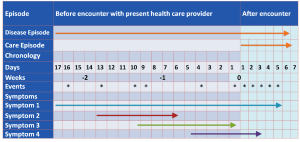

Care Episodes and Phases of Care

For better understanding, the period within which care is given can be divided into

- Episodes,

- Phases,

- Sessions,

- Visits,

- Events,

- Encounters,

- Tasks.

The Care Episode

A care episode is defined as the period within which the management of one particular disease or a health problem affecting a patient takes place i.e. beginning with the time of first contact with a health care practitioner to the termination of care due to resolution of the illness/problem, the patient’s decision to discontinue receiving care or death of the patient. During an episode, the patient may make several visits and during each visit he or she may experience many events. The most important events are encounters with various health care providers, during which subjected to many interventions or experience certain incidents.

Phases of Care

The care episode can be divided into phases of the various care delivery process. The phases can be categorized loosely into:

- Phase of diagnosis or problem identification and elaboration,

- Phase of initiation of treatment and adjustment of therapy,

- Phase of maintenance of therapy, monitoring, review and adjustment of the care plan and therapeutic strategies,

- Phase of assessment of effectiveness and continuation-termination of therapy.

The duration of each episode is variable. It can be limited to one day or even a lifetime. It would not be uncommon for all the phases to be completed within the same day. For incurable diseases, the fourth phase may terminate only with the patient’s death.

The phases coincide with the care processes or the patient care workflow shown below:

Clinical Care Workflow

Clinical care providers follows a common way of performing heir work. Tasks are done in steps which can be sequential or synchronous (done at the same time). A task generate data which is used as input as input for the next task or for making decisions on how to proceed. If the task is unsuccessful (i.e. the desired result is not obtained) the task is repeated. Even if successful, it necessary to repeat the tasks before the final outcome can be achieved. The task of information gathering need to be repeated as conditions change with the progress of the disease and the response to treatment. Hence, clinical care processes are said to ne cyclical or iterative in nature.

Visits, Encounters and Events

A clinical visit begins when a patient presents him/herself to a health care service facility and ends when he/she leaves it. It can be to any one of various care settings including Emergency, Outpatient, Daycare, Inpatient or Teleconsultation. A home visit is also a visit.

In a hospital, services are provided usually by Clinical Service Units belonging to Clinical Departments. Each visit consists mainly of various encounters with a care provider. During an encounter, the patient receives part or all of the clinical care services. These include planned events such as consultation, performance of diagnostic procedures (investigations), monitoring, treatment, nursing care and other clinical activities. The patient may be involved unplanned events (e.g. incidences, complications and another illness).

DATA GATHERING METHODS AND DATA SOURCES

Data Generation

Data arise when certain processes are performed or events happen. In clinical practice, data is generated by the following basic actions:

- Acquire from existing sources,

- Interview,

- Observe,

- Inspect,

- Count,

- Measure,

- Examine,

- Test,

- Capture of data generated by machines

- Manipulation of existing data (calculate, compute, analyze, interpret and conclude).

All clinical care processes generate data. Clinicians obtain the data, record them as notes, results or charts by performing the processes listed below.

- Interview the patient (history taking),

- Perform a physical examination,

- Perform simple tests (point of care tests – POCT),

- Perform investigations including laboratory, imaging, endoscopic and others,

- Review available data, determine the diagnosis and plan the case management,

- Implement care as planned,

- Monitor and assess the patient.

Machines when used to perform functions like tests and monitoring also generate data.

In a paper record the documented information is compiled in a file, in chronological order and appears exactly as they are written. In a computerized system, besides keeping it as a chronological record, the data may be categorized, indexed, put together and displayed as views that serves specific purposes.

Choice of Methods

How and when data is gathered depends on the situation and type of case. The sequence need not necessarily follow the standard clinical workflow described above. Sometimes opportunities arise unplanned, e.g. a patient describes something that the care provider intends to ask later or a sign of another area is noticed when examining a certain area. However, the way the data is presented need to follow a standard format so that information can be easily sought and understood by everyone involved in the care of the patient.

At the first encounter, the crucial reason for gathering data is to obtain sufficient information to make a diagnosis and act upon it.

In emergency situations, there is a need to identify the problem quickly. Often the physical examination is performed before history taking. Sometimes, a biochemical test (e.g. blood sugar level using a point of care testing method) is done straight away. Using a Pulse Oximeter to determine the oxygen saturation of the peripheral blood (SpO2) is another example. However, subsequently a complete history need to be taken and a full examination performed to derive a more accurate and comprehensive diagnosis and to get to know more about the patient.

Information gathering is a continuous process. All clinical processes generate data. The data generated are captured on paper in free form or using templates. In a Clinical Information System electronic forms are used for data entry. The forms contains data fields for inserting data values of data elements anticipated to be sought by the care provider. Indeed the form can be used as a guide as to what data to be collected for different diseases at different points in the care process. The clinical process itself often determines how and what data is collected. Unexpected events or incidents and their effects need to be described as they happen. Yet, some active data gathering must be done to ascertain what actually happens, where, who are involved and the reasons why they occur.

The experienced clinician would be aware which data need to be recorded for immediate use and which will be required for later use. The need for some data becomes obvious only when the occasion arrives. For example, when using a drug to treat a disease some information may be required regarding allergy to drugs or the patient’s preference.

Computation, analysis and interpretation of existing data results in new (derived) data. This facility can be used to derive scores or assign patients to predetermined groups for purposes of severity grading, risk assessment and prognosis.

Content and Characteristics of Clinical Data

Content

The data regarding the patient includes:

- Symptoms experienced by the patient or observed by people close to him and by on-lookers,

- Signs discovered or elicited by the care provider,

- Observations made by qualified care providers,

- Parameters measured by monitoring equipment,

- Results of clinical tests,

- Images from imaging examination & reports made,

- Physiological tests,

- Laboratory tests,

- Biochemistry

- Immunology

- Microbiology

- Haematology

- Histopathology and Cytology

- many others

Data Characteristics

Subjective Data

Information provided by the patient and their carers though subjective is of paramount importance because it describes personal experiences including past events, not obtainable from any other source. It is also the means for the patient to express his/her problems and needs. However, the clinician should be aware that some of the information provided is inadequate or may not be very reliable. Occasionally patients hide the truth or make up stories.

The patient’s description of the sequence of events enables the care provider to compare it with its usual presentation in the natural history of a known disease. This will aid in determining diagnosis, stage of the illness and its severity.

Objective Data

The care provider must attempt, with the utmost possible effort, to obtain objective information through the use of more reliable methods such as physical examination (direct observation, palpation, auscultation etc.) and tests. Usually, the diagnosis becomes increasingly more accurate as care progresses as more objective data are obtained from monitoring and investigations. Tests that give specific objective information regarding a disease and used to clarify the diagnosis are called diagnostic investigations.

DATA FROM EXISTING SOURCES

Review of Past Records

It is mandatory for the clinician to establish whether the patient has received care before the visit. If it is from the same hospital or clinic, the patient’s medical records (paper or electronic) should be retrieved and reviewed. Valuable information can be obtained regarding previous episodes of illness, visits or encounters. A visit summary or discharge summary written by the care provider managing the patient during visits, if available, is invaluable for ensuring effectiveness, continuity and safety of care.

Access to Data from other Facilities and Care Providers

The patient seeking a consultation may bring along information regarding care in the health care facility where they were previously managed in the form of:

- Referral letters,

- Notes / printouts of results and reports (Histopathology and Radiology Report)

- X-ray Films or Images in digital format

- Case summary

- Patient carried records

Information from these documents should be incorporated into the patient’s history. It is also important to retain original hard copies or digital scanned images of them.

INTERVIEWING THE PATIENT

Interviewing the patient (taking a history) is an activity of obtaining information for some of the purposes mentioned earlier and elaborated below. The data includes:

- Data regarding Identification, demographics and social background

- History of present illness,

- Complete information regarding the health status of the patient including past illnesses

- Information regarding the patients understanding of his/her illness and attitude towards it.

Method

Identification, Demographics & Social Background

Much of the data regarding identification, demographics and social background would have been recorded by clerical staff at the time of patient registration. The clinician, however, needs to verify that these are accurate and add on whatever appears to be relevant.

History of Present illness

The main purpose of the interview is to obtain the history of the present illness. “History” here denotes happenings that the patient or others are aware of, occurring over a time period. It has two elements i.e.

- Sequence of events (happenings)

- Symptoms

To any person, being sick is an occasion when he/she experiences one or more symptoms or notice something unusual about him/herself. The onset of the illness may be heralded by an event which may be its cause, for example an injury. It may actually be the effect, for example a fall after losing consciousness. Sometimes, the event is not related to the illness but the patient may think otherwise.

By taking a clear history of the symptoms and the events surrounding it, the clinician hopes to know the following:

- The manifestations and development of the illness, hence to determine the most likely pathology or disease causing it (the diagnosis),

- The existence and severity of symptoms and the need for relief,

- The extent of disability or impairment of a function (physical, psychological, social and spiritual) and the need to restore it

- The patient’s insight into his/her illness

The Asymptomatic Patient

Sometimes patients who seek care may not have symptoms. Patients may turn up because they are worried or suspicious (e.g. a disease that runs in the family), after doing a test voluntarily or as part of a screening programme. A review of symptoms of various systems still needs to be done.

Clarifying the Sequence of Events

The habit of asking the patient ‘Why do you come to the hospital?’ is unhelpful and confusing to the patient. The most likely answer that will be obtained would be “I come to get treatment” or “I come to see the doctor”. In Western culture perhaps it’s a social custom to say “My dear, what brings you to see me?” or “To what, do I owe the honour of this visit?” and it would be clearly understood by the patient. It does not work so well in other cultures.

Instead, it would be better to ask the patient directly “When did you first feel unwell?” followed by “What makes you think so?” Depending on the type of symptom and acuteness of the onset the patient may give an exact time or some vague period. The patient may even say he/she is healthy except for the appearance of some swelling or mass or other changes in appearance which is noticed either by himself or people around him.

Understanding the Natural History of a Disease

The natural history of a disease refers to development of a disease over time, without medical intervention, characterized by the pathogenesis, the different effects it has on the patient leading to various clinical manifestations, progress and endpoints. A disease’s presentation is often typical but atypical presentations do occur. The overall pattern of progress may be described as:

- Symptoms increasing or decreasing in severity

- Episodes vs. Disease free periods

- Attacks or Exacerbation vs Sub-clinical presentation,

- Remissions vs. Relapses, Recurrences of previous illness

Patients seek treatment at different stages of their illness.It is not sufficient to understand only the “classical” presentation of an illness but also the different modes of manifestation at the different stages.

Symptoms: The Manifestations of Illness

A disease often manifests as a set of symptoms (the symptom complex) that is often characteristic. The more serious or prominent complaints are termed as the main or chief complaints. Information need to be obtained regarding each symptom separately; but knowing the relationships of the symptoms (the symptom complex) is just as important. In taking a history, the clinician attempts to establish the development of the disease over time.

Onset, Development and Duration of Illness

For a given disease, patients may seek help at different stages after the onset of the disease. Manifestation of the disease will vary depending the stage (early or late) at presentation and hence its severity. While a disease usually have a typical set of symptoms and signs, there is actually a wide spectrum of presentation.

By knowing the symptoms and their development, the clinician is able to relate the illness with known pathological processes. It is important to determine when a symptom actually starts (onset) and whether it is triggered by an event. Symptoms that appears and progresses slowly at the initial stage is said to be insidious in onset and relate to a disease that develops gradually. Symptoms sudden in onset are usually indicative of acute illness caused by pathologies that develops quickly such as acute inflammation, obstruction, perforation, sudden ischaemia, bleeding or trauma.

It is important to determine when the illness actually starts. From the patient’s point of view, the duration of the illness is from the time the first symptom starts to the time he/she has an encounter with the clinician. He/she may be aware of other episodes or other similar symptoms but may not relate them to the current illness. The clinician need to ask the patient about any changes to his/her health during the period prior to the illness. The duration of illness is a major factor in determining severity of illness. As a rule, the severity of symptoms especially the development of complications increases with duration. Yet, there are instances where time has allowed the healing processes to proceed and symptoms have become reduced or altered. This may not mean that the disease has healed or aborted. Patients nay have taken some treatment from elsewhere or on their own. This may alter the presentation.

The duration taken to seek treatment reflects on the patient’s attitude to illness and medical care. This knowledge is of use to the care provider in determining the right approach to the patient.

Progress of Symptoms

The occurrence of symptoms reflect the progress of the disease. A set of symptoms may occur for a certain period and then abates before occurring again at another period. Each period can be thought of as an episode of the illness and the illness is said to be episodic or recurrent (note that the disease episode is different from the care episode). Patients often do not consider milder symptoms to be part of the same illness. It is likely that the illness may have occurred earlier than the patient’s own estimation.

If the symptoms of a chronic illness become dormant, mild or infrequent for a considerable period, the illness may be considered to be in remission. If a disease remains but does not manifest in symptoms it is said to be sub-clinical. If a patient develops symptoms again after the illness is thought to have been cured, the new episode may be considered as a relapse or recurrence. An attack or exacerbation is said to occur if after being sub-clinical, symptoms become suddenly perceptible, worrisome or worsened. Many diseases are episodic in nature i.e. periods of remission are followed by recurrences (e.g. migraine).

In an acute illness, a symptom may vary in intensity (wax and wane). It may appear and then fade only to appear again after a short duration (said to be intermittent). It may also disappear completely for a significant interval but appears again with the same intensity (said to be remittent)

The essence of history taking is relating events and symptoms to time. As a basic requirement, the clinician needs to possess theoretical knowledge regarding the natural history of a disease i.e. the development of a disease without medical intervention and the different possible effects it has on the patient over time. It is important to know whether symptoms occur simultaneously or sequentially and whether they are continuous or recurrent. The clinician is then able to relate the various clinical manifestations, complications, progress and endpoints with pathogenesis of the disease. It is good to know if the patient has taken some medication on his/her own or has obtained some sort of treatment elsewhere because these will alter the manifestation of the symptoms.

Often, patients volunteer information regarding their previous encounter with other care providers. They may also provide the diagnosis and describe findings of tests performed. The clinician should make a note of these but should take his/her own history and make his/her own conclusions.

Disease Episode and Care Episode

Morphologic and Physiologic Effects

Symptoms can be felt in a specific organ, at an anatomic region or generally.

The anatomical location of the symptom may give an idea of the organ or organs involved. It may suggest the tissue type involved e.g. whether it is skin, muscle, nerve or blood vessel. Symptoms may also relate to a particular physiologic function. It may also indicate the probable pathology.

General/Systemic Symptoms

General symptoms are usually manifestations of the derangement of one or more physiologic systems. It is expected even if the disease is limited to a specific organ. Therefore, if symptoms expressed by the patient appear to be confined to an organ or site, the general symptoms expected with the pathological process or malfunctioning of the organ should be looked for. Diseases originating from an organ may have spread or extended to the surrounding region by the time the patient seeks help. The history becomes the means for the clinician to ascertain the organ or physiologic system at the beginning of the disease.

Symptoms of Specific Organs and Sites

It would be desirable for the clinician to be able to work out a postulate of the site of illness, the physiological system or organ affected and the aetiology based on the symptoms. This requires a good knowledge of regional anatomy and physiology.

The Symptom Complex

An illness may manifest as a single symptom or a set of related symptoms. Besides describing each symptom according to the characteristics mentioned earlier, the composition, association and relationship of symptoms need to be clarified. A set of symptoms, occurring together is termed as a symptom complex. The combination is dependent on the anatomic site, physiological system affected and pathological process and is often typical for a particular disease or disease group. termed clusters. Symptoms can appear concurrently or sequentially. The order and interval of appearance of symptoms are important indicators of the nature of the illness as is their progress and remission. A set of symptoms appearing within a short period is often called a cluster. A symptom complex ca e taken as an early working diagnosis based on which further actions can be planned.

Further reading: link

INFORMATION THROUGH PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Purpose of Physical Examination

The main purpose and objective of a physical examination is to discover changes in:

- The morphology (appearance) of the whole patient, relevant anatomical regions and organs

- The status of the physiologic functions (unchanged or deranged) of various systems or organs

In doing so, the clinician also establishes whether there are variations of these from normal and confirms those that are normal or probably unaffected by the illness.

Approach to Physical Examination

The clinician can take two approaches to physical examination i.e.:

- Examination based on Postulate or Hypothesis derived from History of Illness

- Systematic Review

Each approach has its merits and a combination of both is the right approach. In a situation where initiation of treatment need to made quickly, a quick examination of the part or system that would provide the most useful/relevant information to make a diagnosis and assess the patient,s condition should be done. A more complete examination can be performed when the patient is more stable.

In a less urgent situation, a complete examination is performed from the start. The luxury of ascertaining the morphology and function of various organs and system without missing less obvious signs, will facilitate the derivation of an accurate diagnosis

Method

Findings on examination are often referred to as signs. They can be either discovered or elicited. The astute clinician uses all his/her senses of the examiner (sight, touch, smell and hearing) with the exception, perhaps, of taste.

The methods used in physical examination are:

- inspection and observation

- palpation

- percussion

- auscultation

Using Clinical Tests to Elicit Signs

Clinical tests are used to determine whether the patient’s response to stimuli is normal or abnormal. Such tests use various mannoeuvres or manipulations and stimulation of the patients with physical agents, situations or drugs. Tests may assess behaviour, functions and characteristics.

(details are best obtained from books on Clinical Methods.)

Examination Guided by Symptoms

When substantial facts have been obtained through history-taking, then it is possible for the clinician to consider the illness and its causes as a postulate or hypothesis (the symptom complex) and use it as the guide as to the signs he/she should be looking out for. Hence, the areas to be examined and the signs to look for are those expected in that particular syndrome or disease. A good knowledge of the common manifestations of the disease being suspected is essential.

Note that failure to find the signs do not disprove the hypothesis because some effects of illness especially at the early stage are subtle and may be detected only by various laboratory-based tests, imaging techniques, endoscopy or modalities. Repeat examination at a later time may prove to be useful.

The Clinical Syndrome

Signs also often manifest as a set. These taken together with the set of symptoms (the symptom complex), constitutes a ‘Clinical syndrome’. By knowing how various diseases manifest, the clinician can determine which anatomical site and physiological system to concentrate on.

General Examination

In the general examination, the patient as a whole is assessed. It is used to seek the following:

- The manifestations of the changes in the health status of the person as a whole

- The obvious or easily obtainable signs relating to various physiologic systems i.e. cardiovascular, respiratory, neurologic, renal, and musculoskeletal systems

Being a general examination, it is not meant to be use to elicit signs regarding a particular organ. It is incorrect to begin by saying “on examination of the hand”. Instead the correct expression is the “peripheries are warm” after examining both the fingers and toes. Pallor can be a result of reduced haemoglobin, decreased oxygen saturation or poor perfusion. It should be described as “the conjunctiva, mucous membranes and fingers are pale”, instead of saying “on examination of the eye: the conjunctivae is pale”. It is not an eye examination, it is a general examination. Peence of derangement in an organ should be sought for in other organs.

Generally, each system is characterized by a typical set of signs. However, a sign may emerge as a result of derangement of different different systems or due to different disease processes.

Systematic Review

Signs may be present even if the there is no related symptom. This may be because the patient was unaware of it or would not divulge its presence. There are also signs that appear before symptoms arise. An alert clinician should be able to discover these signs as part of a systematic review. This consists of examining each region and system in turn to discover anomalies. It may not be detailed and exhaustive initially but may have to be repeated later if the diagnosis remains unclear.

Hence, despite the postulate made after history taking the clinician needs to have an open mind and consider all possibilities. The discovery of one or more signs will lead to a different postulate and signs expected of that postulate should be looked for. Indeed, the patient should be queried about the presence of expected symptoms related to the sign and would often then recall symptoms or events he or she had not mentioned earlier.

Method of Physical Examination

When performing the physical examination, the clinician uses various senses to discover the morphologic appearance or physiological status of a patient. These include the use of:

- Sight: to inspect the morphology (colour, shape) and observe the physiology (movement)

- Sensation: to determine texture, consistency, vibration, temperature, etc)

- Hearing: to listen for normal and abnormal sounds

- Sense of smell: to detect abnormal odour

Inspection

To inspect means to look once but thoroughly. The parts or organs to be inspected need to be exposed. The purpose is to detect changes in the appearance of visible organs or body regions including skin, mucous membranes, appendages and protruding organs. Although only superficial parts can be inspected, deductions can be made regarding deeper structures or certain functions (e.g. ptosis due to inability to move eyelid).

The characteristics of each organ or part to be inspected include:

- Colour

- Surface appearance

- Shape

- Rough Size

- Abnormal or additional features not seen when the organ is normal (e.g. discharge)

The clinician seeks for and describes the difference in these features from that expected of a normal person. Both inspection and observation are best done first without prior disturbance or interference. In children, this may be best done when they are asleep or are distracted.

Observation

To observe is to look for changes in function and appearance of an organ or body region over a time period. The functions that may be observed include:

- Overall demeanour, facial expression, gait and posture

- Conscious level (speech, spontaneous movements)

- Movement (limbs, lips, eyelids, nostrils, the head)

- Breathing

- Beating of the heart

- Pulsation of arteries

For functions occurring at a regular frequency (breathing, heart beat and pulsation), the rhythm and intensity can be observed and the rate counted. Test of Function by Observation

The state of some functions are not evident by passive observation but can be made apparent by instructing the patient to perform certain maneuvers. This purposeful performance (e.g. movement) is said to be “active” function tests. These demonstrate ability or disability of certain functions (e.g. opening eyes and moving them side to side / up and down).

Palpation

Palpation is the use of tactile sensation of the fingers and hand to detect characteristics that include:

- Change in temperature

- Surface texture

- Shape

- Contour or edge

- Extent or size

- Consistency

- Mobility

- Spontaneous movement of organs

- Location, depth and relationships

The act of palpation itself can also act as a test e.g. of tenderness and mobility.

Only signs in organs accessible to the fingers can be elicited. A gentle light superficial palpation gives different information from deep palpation. A knowledge of surface anatomy helps in determining the likely organs from which the signs originate. The knowledge of cross-sectional anatomy help indicate which anatomical layer the lesion is located i.e. within the skin, subcutaneous tissue, the muscular layer, bones or body cavities. Certain characteristics such as extent can be inferred when even when the whole organ or mass cannot be reached based on the clinician’s knowledge of anatomy or physiology.

In deep palpation the force exerted should not exceed that which would cause discomfort to the patient and he/she should be forewarned. The presence of tenderness should be anticipated and the presence of pain should be asked for from the patient. Light palpation may be performed in the presence of slight tenderness and the patient should be warned regarding it. No further palpation or percussion should be done in the presence of tenderness. The clinician will have to use other means such as ultrasonogram or examination under anaesthesia to elicit the signs.

Auscultation

To auscultate is to listen to sounds made by various organs. A normal finding is as important as an abnormal finding. Changes can be of the frequency, loudness, tone and pitch of usual sounds. Abnormal sounds can occur in certain pathologic changes e.g. pericardial rub, pleural rub, crepitation and murmurs.

Local, Regional and Generalized Changes

Each medical discipline has developed specific ways of examining various organs and systems. Source of guides on Guides on this subject matter is extensively available in print and electronic format and for general as well as specific areas for example on the eye..

The examination can be systematic or directed by the history or other available data. In some cases speed of obtaining relevant findings is essential. However, full examination must be completed even if it done at multiple instances rather than a single examination.

A Set of Signs and Symptoms: The Syndrome

A set of associated symptoms and signs occurring together is termed as a syndrome It is often typical of a particular disease or disease group.. Again, like the symptom complex, the combination is dependent on the anatomic site, physiological system affected and pathological process.

Documentation of Data from Clinical Methods

The way data obtained from interview, examination and clinical tests as recorded on paper has evolved from an unstructured to more structured formats. In earlier times care providers write on a blank sheet of paper and records whatever they think are important findings. Later, they may follow a certain order such as SOAP i.e. subjective data (from the interview), objective data (from physical examination and tests), assessment (actually formulation of diagnosis) followed by plan of care. Further to that, if the type of disease and the region or system involved is known then the data elements and even the results for anticipated findings may be pre-printed for the care providers to fill in.

Even when computerized forms may take on the form of empty pages, with or without headings, where data can be typed in However, the use of electronic forms for data acquisition allow for the structure to be more definite and content to be more relevant. The use of structured data allow for data aggregation, analysis and interpretation, features that can enable the provision of decision support. This is further discussed in the article on Clinical information System under the topic on data acquisition.

More complex forms can be structured such that documentation follows the data gathering processes performed by the care provider. The data can be in compartments arranged in a certain order applicable to history taking and

For physical examination it may have the structure as below:

- General morphology

- Specific finding

- surface appearance (colour, texture, breach of skin, discharges)

- tenderness,

- presence of mass etc.).

For each of these, means of documenting expected characteristics can be provided such as:

- Location, extent

- Specific function

- Specific morphology

- The mass or swelling

Clinical Information From Simple tests

augment

Point of Care

Need some degree of expetise

Methods available

Simple or requires use of instruments.. Can be prtoed easily without complex equipment. Blood g,ucose measurement is ubiquitous.

Content and Characteristics of Data Obtained

- of care including performance of procedures and use of drugs

- To monitor and assess the progress of the illness, the effectiveness of treatment and the side effects of treatment

as in patient interview and physical examination. POCT tests are confined to only uncomplicated and inexpensive investigations.

- Glucose

- Blood gas analysis/electrolytes Blood gas analysis/electrolytes

- • Activated clotting time for high dose Activated clotting time for high dose

- heparin monitoring heparin monitoring

- • Urine dipsticks, including pregnancy Urine dipsticks, including pregnancy

- • Occult blood Occult blood

- • Hemoglobin Hemoglobin

- • Rapid strep

Cardiac markers Cardiac markers

• Drug/toxicology Drug/toxicology

• INR

• Heparin Heparin

• Coagulation for Coagulation for hemostasis hemostasis

assessment (TEG) assessment (TEG)

• D dimer for

thromboembolism thromboembolism

• Magnesium Magnesium

• Lactate Lactate

• Transcutaneous Transcutaneous

bilirubin bilirubin

• Lipids

• Hemoglobin A1c Hemoglobin A1c

• Microalbumin Microalbumin, creatinine creatinine

• HIV

• Influenza Influenza

• Helicobacter pylori Helicobacter pylori

• Other bacteria

Leave a Comment